Building Exospecies AI: Parsing

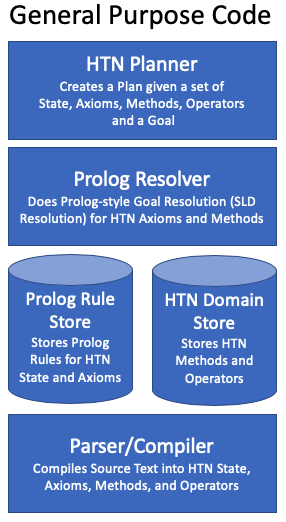

In building Exospecies I ended up having a lot of different types of files that needed to be parsed: HTML files, settings files, Prolog files, etc. I went and researched the best tools for parsing (and there are many!) but they all seemed like big black boxes that I was going to spend a lot of time debugging, understanding, learning how to use, etc. I wanted something that was really simple, lightweight, debuggable, etc. Plus, I didn’t think I’d really understand any of them if I didn’t understand how parsers worked in the first place. Thus, the Inductor Parser Engine was born! It is the bottom layer of the Exospecies HTN Architecture:

The code for the parser is available on GitHub. This blog post will describe how to use it.

Creating a Grammar

IndParser is called a PEG Parser, which is a very simple to understand and implement type of Recursive Descent Parser. I chose this approach because the way you express your parser rules is very readable and understandable and it is straightforward to implement.

It is written in C++ so it can be ported across many platforms (PC, Mac, XBox, etc), and uses C++ Templates because I found them to be a very natural way to express grammars.

To create a grammar using IndParser, you write a set of rules that describe what you expect to find in the string you want to parse. For example, if you want to parse name/value pairs like this:

setting = 5;

You would declare what you are looking for, in the order you expect it:

- a text string (e.g.

setting) - followed by an optional space

- followed by the actual character

= - followed by an optional space

- followed by a number

- followed by an optional space

- followed by the actual character

;

Nice and easy! Here’s how you would write the grammar using the built-in IndParse C++ template classes:

class NameValueRule : public

AndExpression<Args

<

// a text string (e.g. `setting`)

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>

>,

// followed by an optional space

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

// followed by the actual character `=`

CharacterSymbol<EqualString>,

// followed by an optional space

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

// followed by a number

Integer<>,

// followed by an optional space

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

// followed by the actual character `;`

CharacterSymbol<SemicolonString>

>>

{

};

You declare a class that will be your rule (we called it NameValueRule) and derive that from a built-in rule which is usually AndExpression since you usually have a sequence of things you require. AndExpression says that everything it contains must be there, in that order. OneOrMoreExpression says that everything it contains must happen at least once, but more is fine. Etc. The magic of IndParse is that you write rules exactly like you think about parsing the text. Very readable and easy to write. The rest should be self explanitory.

Because this is using C++ Templates, there is some extra goo you have to put in. For example, all of the built in rules normally a first argument that is “the type of thing you are looking for”. Rules like AndExpression and OrExpression need more than one thing. So, we use a special template class called Args, which can take many. You can see it above right after the AndExpression< in the example.

Parsing Using the Grammar

To actually run the grammar on a string, you call the static TryParse() method of the class you created and pass in a Lexer class. The Lexer class does the work of reading the characters in the string and keeping track of position as the rule gets executed:

// Open a Lexer on the test string

string testString("setting = 5;");

shared_ptr<Lexer> lexer = shared_ptr<Lexer>(new Lexer());

shared_ptr<istream> stream = shared_ptr<istream>(new stringstream(testString));

stream->setf(ios::binary);

lexer->Open(stream);

// Actually parse it

shared_ptr<Symbol> tree = NameValueRule::TryParse(lexer, "NameValueRule");

if(tree != nullptr)

{

// Success! Let's make sure we got what we expected

// FailFastAssert() just aborts the process if it isn't true

// When done, `tree` will contain a tree of objects that matches

// the tree you created with your rules

FailFastAssert(tree->symbolID() == SymbolID::andExpression);

// You can use ToString() on a symbol to recover the whole chunk of text it parsed

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->ToString() == "setting");

// Or you can walk through its children to get each piece

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->symbolID() == SymbolID::oneOrMoreExpression);

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->children()[0]->symbolID() == 's');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->children()[1]->symbolID() == 'e');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->children()[2]->symbolID() == 't');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->children()[3]->symbolID() == 't');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->children()[4]->symbolID() == 'i');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->children()[5]->symbolID() == 'n');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[0]->children()[6]->symbolID() == 'g');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[1]->symbolID() == SymbolID::whitespace);

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[2]->symbolID() == '=');

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[3]->symbolID() == SymbolID::whitespace);

// There are children under the Integer too, but we'll ignore them for now

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[4]->symbolID() == SymbolID::integerExpression);

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[5]->symbolID() == SymbolID::whitespace);

FailFastAssert(tree->children()[6]->symbolID() == ';');

}

else

{

// Failure: lexer will give a best guess error message

string error = lexer->ErrorMessage();

}

When done, tree will contain a tree of objects that matches the tree you created with your rule as shown above. Each Symbol has a unique ID to make it easy to identify. CharacterSymbols have an ID which is the actual character that got parsed. You can walk the tree using the children() method. Here’s the tree more conceptually:

-[andExpression]

- [oneOrMoreExpression]

- s

- e

- t

- t

- i

- n

- g

- [whitespace]

- =

- [whitespace]

- [integerExpression]

- 5

- [whitespace]

- ;

Tuning a Grammar

After you end up walking these trees a bunch, two things become obvious:

- A lot of crap in the tree like

=and;and whitespace is just there for the author or the parser, you don’t actually care about it when processing the tree. All you really want out of the statementsetting = 5;issettingand5. - It would be nice to use SymbolIDs that have meaning for your actual rule in place of IDs like

oneOrMoreExpression.

The first issue is solved by a concept called “Flattening”. Most rules have a template argument called flatten which takes a value from the FlattenType enum:

// Allow you to control "flattening" which controls

// what the tree looks like if the node is successful:

// - Flatten means take this symbol out of the tree and

// reparent its children to its parent (which is useful

// for nodes that are there for mechanics, not the meaning

// of the parse tree)

// - Delete means remove this symbol and all children

// completely (which you might want to do for a comment)

// - None means leave this node in the tree (for when the

// node is meaningful)

enum class FlattenType

{

None,

Delete,

Flatten

};

To take advantage of Flattening, you have one more step after parsing:

vector<shared_ptr<Symbol>> flattenedTree;

tree->FlattenInto(flattenedTree);

Turns out the default is FlattenType::Delete on OptionalWhitespaceSymbol and CharacterSymbol because there are just there to delimit things and you mostly don’t want them at the end. Both OneOrMoreExpression and AndExpression are set to FlattenType::Flatten which means they will remove themselves from the tree since they are just helpers and not necessarily semantically meaningful on their own. Integer is set to FlattenType::None so there is a node in the tree that represents the Integer.

So, after running FlattenInto() the tree will no longer be a tree, it will be a vector of trees and will look like this:

- s

- e

- t

- t

- i

- n

- g

- [integerExpression]

- 5

Much simpler! However, the string settings got flattened all the way to the top. I’d rather have it under a node so I can distinguish it from other items easily. Let’s change the FlattenType of that, AND give it a special ID to show how our second issue above gets solved.

Here’s the updated rule:

class MySymbolID

{

// Choosing your custom IDs starting with CustomSymbolStart

// makes sure you don't conflict with the built-in rules

public:

static const unsigned short SettingName = CustomSymbolStart + 0;

};

class NameValueRule : public

AndExpression<Args

<

// Change to not flatten and give a custom ID

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>,

FlattenType::None, MySymbolID::SettingName

>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<EqualString>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

Integer<>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<SemicolonString>

>>

{

};

Now if we parse and flatten, we get this tree:

- [SettingName]

- s

- e

- t

- t

- i

- n

- g

- [integerExpression]

- 5

Much nicer!

Full Example Code

Here’s the full code to create the rule and parse it, getting those two values out:

class MySymbolID

{

public:

static const unsigned short SettingName = CustomSymbolStart + 0;

};

class NameValueRule : public

AndExpression<Args

<

// Change to not flatten and give a custom ID

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>,

FlattenType::None, MySymbolID::SettingName

>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<EqualString>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

Integer<>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<SemicolonString>

>>

{

};

void ParseString()

{

// Open a Lexer on the test string

string testString("setting = 5;");

shared_ptr<Lexer> lexer = shared_ptr<Lexer>(new Lexer());

shared_ptr<istream> stream = shared_ptr<istream>(new stringstream(testString));

stream->setf(ios::binary);

lexer->Open(stream);

// Actually parse it

shared_ptr<Symbol> tree = NameValueRule::TryParse(lexer, "NameValueRule");

if(tree != nullptr)

{

// Success! Now flatten it

vector<shared_ptr<Symbol>> flattenedTree;

tree->FlattenInto(flattenedTree);

// Because it succeeded, we can assume the rules all worked

// and the tree is in the shape we expected

FailFastAssert(flattenedTree[0]->symbolID() == MySymbolID::SettingName);

FailFastAssert(flattenedTree[1]->symbolID() == SymbolID::integerExpression);

// And we can just call ToString() to recover the values we want

string settingName = flattenedTree[0]->ToString();

FailFastAssert(settingName == "setting");

string settingValue = flattenedTree[1]->ToString();

FailFastAssert(settingValue == "5");

}

else

{

// Failure: lexer will give a best guess error message

string error = lexer->ErrorMessage();

}

}

Creating Multiple Rules

But wait! What if you want settings to contain more than just integers? Something like "setting = foobar;" or "setting = 5.6", perhaps? Turns out you can create new rules and reference them with other rules to make things as complicated as you want. Let’s create a rule called SettingValue and let it contain a text string OR an integer OR a float:

class MySymbolID

{

public:

static const unsigned short SettingName = CustomSymbolStart + 0;

static const unsigned short SettingValue = CustomSymbolStart + 1;

};

class SettingValue : public

// We want this Symbol to simply contain the value it parses

// with no other structure. So, we Flatten each of the options

// but don't flatten the top level node

OrExpression<Args

<

Float<FlattenType::Flatten>,

Integer<FlattenType::Flatten>,

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>

>

>, FlattenType::None, MySymbolID::SettingValue>

{

};

class NameValueRule : public

AndExpression<Args

<

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>,

FlattenType::None, MySymbolID::SettingName

>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<EqualString>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

// And we we can reference that rule from

// within this rule

SettingValue,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<SemicolonString>

>>

{

};

That is how you build up a more complex grammar: defining rules and using them within other rules. The parse tree for "setting = 5" would look like this using that rule:

- [SettingName]

- s

- e

- t

- t

- i

- n

- g

- [SettingValue]

- 5

or if we parsed foo=-3.5; it would look like this:

- [SettingName]

- f

- o

- o

- [SettingValue]

- -

- [integerExpression]

- 3

- .

- [integerExpression]

- 5

Note that the Float rule leaves the integerExpression structure before and after the decimal point intact so that you can easily interpret it if you need to. If not, you can just call ToString() on the SettingValue node and get the string -3.5.

Error Messages

It turns out that giving a good parse error is hard since the code can’t tell what you meant to type. However, the IndParser uses a heuristic that seems to work out pretty well: Assume that the error is in the deepest (meaning farthest down the tree) rule that was tried and failed. The idea being that we made the most progress there and so that’s probably where the error occurred.

To make it easy to return meaningful error messages, most of the built-in templates have a staticErrorMessage argument that you can set. If parsing fails on that rule, that is the error message that will be shown. I find that putting something like “Expected a [whatever the rule is for]” is usually a fine error message.

Common Pitfalls

Your grammar needs to consume the entire string or it will fail.

If you tried the above example with the string "setting = 5; " (note the space after the ;), it will fail. There is no rule for whitespace after the ; and IndParse requires that your rule parse everything to succeed.

I usually have a rule called “document” to lay out the whole structure of a document. In this case it is simple:

class NameValueDocumentRule : public

AndExpression<Args

<

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol,

NameValueRule,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol

>>

{

};

Compiling

So far we’ve been talking about Parsing, which is taking a string of text and turning it into a set of well structured symbols. Compiling is that plus walking through those symbols and turning them into whatever-it-is-that-you-are-trying-to-build. Taking HTML text and turning it into rendering objects, for example. IndParse can’t do that work for you, but it can give you a handy class called….Compiler which has some handy helper routines for loading files, streams, etc and for collecting errors.

“All” you need to do is create a grammar and then write all the code that is custom for your Compile operation. Here’s the simplest possible example using NameValueRule:

class MySymbolID

{

public:

static const unsigned short SettingName = CustomSymbolStart + 0;

static const unsigned short SettingValue = CustomSymbolStart + 1;

};

class SettingValue : public

// We want this Symbol to simply contain the value it parses

// with no other structure. So, we Flatten each of the options

// but don't flatten the top level node

OrExpression<Args

<

Float<FlattenType::Flatten>,

Integer<FlattenType::Flatten>,

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>

>

>, FlattenType::None, MySymbolID::SettingValue>

{

};

class NameValueRule : public

AndExpression<Args

<

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>,

FlattenType::None, MySymbolID::SettingName

>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<EqualString>,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

// And we we can reference that rule from

// within this rule

SettingValue,

OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<SemicolonString>

>>

{

};

class NameValueCompiler : public Compiler<NameValueRule>

{

public:

virtual bool ProcessAst(shared_ptr<vector<shared_ptr<Symbol>>> ast)

{

// We don't need to check to make sure the vector has two

// elements because the parser will fail if it doesn't.

// ToString() just turns all the children into strings again

// which is exactly what we want since the only children

// under these nodes are the characters for name and value

m_name = (*ast)[0]->ToString();

m_value = (*ast)[1]->ToString();

return true;

}

string m_name;

string m_value;

};

void test()

{

NameValueCompiler compiler;

if(compiler.CompileDocument("somePathInFileSystem"))

{

// Success!

return 0;

}

else

{

// Failure!

fprintf(stdout, "%s\r\n", compiler.GetErrorString().c_str());

return 1;

}

}

The MySymbolID, SettingValue, and NameValueRule classes implement the parser and are described above. NameValueCompiler is the compiler that takes these rules and “processes” them into something useful that isn’t just symbols. That class is derived from Compiler which does the work of TryParse(), getting errors, flattening the tree, etc and just gives you the flattened tree in ProcessAst() (AST stands for Abstract Syntax Tree which is what the tree is technically called). There are several helpers so you can compile strings, streams, etc. And there are helpers for digging through the tree which is what you do when you write this method.

If you look at the (very simple) ProcessAst method above, you’ll see that all it does is look through the symbol tree for the single name/value pair that our rule parses and sets member variables to the values it finds since this is much more natural to deal with. A real name/value pair parser would at least allow for multiple rules, obviously. If you are compiling something more complicated, your method here will also be more complicated.

Debugging

Turns out you don’t always declare rules properly or rules you declare might give unexpected results. If a rule fails, how do you figure out what went wrong?

While I wish using a normal debugger was more helpful, it really isn’t. The parser engine is running all kinds of rules in various different parts of the tree, backtracking, etc. Turns out it is really hard in practice to set a breakpoint that helps you.

Instead there are the obvious things: break down the rule into smaller pieces, comment things out, etc.

If that doesn’t work, the parser has (very verbose!) tracing you can turn on that will output information about each and every path the parser takes so you can see where things fail. To turn on tracing you just put this line before your TryParse() method:

SetTraceFilter(SystemTraceType::Parsing, TraceDetail::Diagnostic);

Let’s modify the rule so that it doesn’t allow whitespace and then try to parse something with whitespace with tracing on.

// NOTE: All whitespace commented out!

class NameValueRule : public

AndExpression<Args

<

OneOrMoreExpression

<

CharacterSetSymbol<Chars>,

FlattenType::None, MySymbolID::SettingName

>,

//OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<EqualString>,

//OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

// And we we can reference that rule from

// within this rule

SettingValue,

//OptionalWhitespaceSymbol<>,

CharacterSymbol<SemicolonString>

>>

{

};

If we then try to parse this string "setting = 5;" and look at our trace output, we get this:

Lexer::Read: 's', Consumed: 1

NameValueRule(Succ) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found 's', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::Read: 'e', Consumed: 2

NameValueRule(Succ) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found 'e', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::Read: 't', Consumed: 3

NameValueRule(Succ) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found 't', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::Read: 't', Consumed: 4

NameValueRule(Succ) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found 't', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::Read: 'i', Consumed: 5

NameValueRule(Succ) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found 'i', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::Read: 'n', Consumed: 6

NameValueRule(Succ) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found 'n', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::Read: 'g', Consumed: 7

NameValueRule(Succ) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found 'g', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::Read: ' ', Consumed: 8

NameValueRule(FAIL) - CharacterSetSymbol::Parse found ' ', wanted one of 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

Lexer::ReportFailure New deepest failure at char 8

NameValueRule(Succ) - 1to2147483647Expression::Parse count= 7

Lexer::Read: ' ', Consumed: 8

NameValueRule(FAIL) - CharacterSymbol::Parse found ' ', wanted '='

Lexer::ReportFailure New deepest failure at char 8

NameValueRule(FAIL) - AndExpression::Parse symbol #1

The structure of the trace output can be a little counterintuitive. You’ll notice it starts out indented, setting out traces from CharacterSetSymbol and then near the end shows a trace from 1to2147483647Expression and AndExpression indented less. The indenting shows how far down the tree the trace is coming from. If you look at our rule above that’s just because these are nested and the engine works its way out, backtracking, when it fails. Also note that our nice OneOrMoreExpression gets renamed to 1to2147483647Expression in the debug output. That’s because the biggest “More” the rule can do is “2147483647” items, since that is the largest positive number a signed 32 bit integer can hold. The parser holds the maximum in a int.

Now for the “deep” analysis: Starting from the top: You can see the Lexer reading characters one by one. You can also see the CharacterSetSymbol rule successfully consuming them. Note where it says NameValueRule(FAIL) near the end. You see it found a space character but wanted something alphabetical. There’s our whitespace bug! (You can also see the Lexer tracking the “deepest failure” for error reporting as described above)

OK, this was an easy one, but you get the idea. Sometimes the only way to debug these is to run the rule and dig through the traces.

What Next?

Go use the parser to do good in the world! The code for the parser is available on GitHub.